Fibromyalgia Syndrome and Chronic Widespread Pain

Posted on January 24, 2024 • 8 minutes • 1543 words

Table of contents

A significant portion of the population experiences persistent and widespread pain, with about 11% in the UK affected. This condition leads to several challenges for both individuals and society, including decreased physical activity, feelings of depression, higher healthcare usage, and a decline in work efficiency. This blog article will primarily discuss fibromyalgia, a key example of a condition characterized by persistent widespread pain and tiredness.

Fibromyalgia, also known as fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS), is a diverse pain-related condition with an uncertain cause. It impacts 0.5–5% of people globally and predominantly affects women. Given that single treatments typically offer limited effectiveness, the European League against Rheumatism (EULAR) suggests a comprehensive treatment strategy for fibromyalgia, tailored to the severity of symptoms, patient capabilities, and other related factors. The goal of this approach is to enhance physical, mental, and social well-being.

Diagnosis

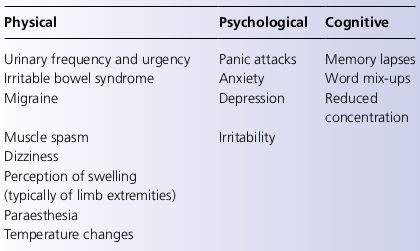

Currently, Fibromyalgia Syndrome (FMS) lacks specific diagnostic tests, so its identification relies solely on clinical assessment. Patients often experience symptoms for two to three years before receiving a diagnosis. Key symptoms include persistent, extensive musculoskeletal pain, stiffness in muscles, fatigue, and non-restorative sleep, without any other underlying conditions like active inflammatory arthritis or endocrine/metabolic disorders. Table 1 outlines various related physical, psychological, and cognitive symptoms.

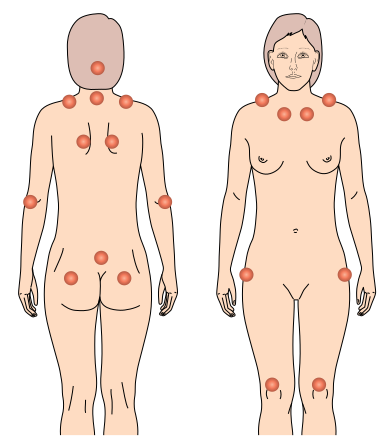

Initially, the 1990 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria were the benchmark for diagnosing fibromyalgia in research, focusing on widespread pain lasting at least three months and sensitivity in 11 out of 18 specific tender points upon applying minimal finger pressure, as illustrated in the figure below:

| Tender points |

|---|

|

However, these criteria have seen limited use in regular clinical settings, likely due to their emphasis on tender points and neglect of other symptoms. In 2010, the ACR introduced a new set of diagnostic guidelines for primary care, acknowledging fibromyalgia’s broad spectrum nature. These revised criteria eliminate the need for tender point exams. They incorporate a widespread pain index (a count of up to 19 specific areas where the patient has experienced pain in the past week) and a symptom severity scale (ranging from 0 to 9), which considers fatigue, unrefreshed waking, and cognitive issues as listed in Table 1.

| Table 1 |

|---|

|

Origins and Manifestations

The origins of fibromyalgia remain a mystery and have sparked considerable debate. Views range widely, with some attributing it to purely physical causes, like a viral infection, while others suggest it’s a manifestation of psychosomatic issues. The consensus now is that it stems from abnormal pain processing in the central nervous system, leading to an inappropriate response to pain. This includes pain triggered by various sensory inputs such as heat, touch, and sound. Factors like heightened central sensitivity, reduced effectiveness of pain-inhibiting pathways, altered levels of neurotransmitters, and psychological stress contribute to this aberrant pain processing. Risk factors might include psychological conditions like anxiety and depression, exposure to viruses, or physical and emotional trauma. Psychological elements, such as past pain experiences, anxiety, and stressful life circumstances, also play a role in the symptoms of fibromyalgia. However, the condition extends beyond pain, with sufferers often dealing with stiffness, exhaustion, and sleep issues, among other physical, psychological, and cognitive effects (refer to Table 1).

A common profile of a fibromyalgia patient is a woman between 30 to 50 years of age, enduring persistent, widespread pain, particularly in muscles and joints. She is likely to suffer significant fatigue, overlapping with chronic fatigue syndrome (with 55% of those patients meeting fibromyalgia criteria). Often, there’s a history of prior physical or psychological trauma. Sleep disturbances, concentration issues, and short-term memory problems are typical. Symptoms are constant and worsen during stressful periods. The patient may experience anxiety and depression, impacting her work and social life. Attempts to relieve pain with analgesics and anti-inflammatory medications usually yield little success.

Diagnostic Process

While no specific tests can definitively diagnose fibromyalgia, it’s crucial to conduct examinations to rule out other sources of musculoskeletal pain. Patients should be informed about the purpose of these tests and understand that normal results are expected. Clinicians play a vital role in affirming the legitimacy of the patient’s symptoms, regardless of the test outcomes, as patients often worry that normal results may undermine the legitimacy of their condition.

Treatment Strategies

Treating fibromyalgia involves informing patients about the disorder and the various treatment options. These include structured exercise programs, activity pacing, psychological therapies, sleep management, and medication. The treatment aims to alleviate symptoms and enhance the patient’s physical, mental, and social well-being. Personalizing treatment plans to suit each patient’s unique requirements is essential.

Patient Education

Explaining fibromyalgia in understandable terms is crucial. Clinicians should convey that the patient’s pain mechanism is overly sensitive, using the patient’s reaction to mild touch as an example. Explanations that resonate with patients, alleviate guilt, and combine psychological and physiological aspects, while offering actionable management strategies, tend to be more effective.

Patients often require guidance, encouragement, and motivation from healthcare professionals to actively manage their symptoms. Managing fibromyalgia involves accepting certain symptoms and limitations and continually self-managing the condition. Setting realistic goals is important to avoid feelings of failure and helplessness.

Local pain management programs may be available to assist patients in coping with their symptoms. Directing patients to resources like the Arthritis Research UK website, which offers patient-oriented information about the condition, can be beneficial.

Incremental Exercise

For those with fibromyalgia, engaging in physical activities can be challenging due to discomfort and fatigue. It’s common for patients to decrease or completely stop exercising because of a fear that it might worsen their symptoms. Activities like swimming, walking, and cycling can effectively maintain muscle health and aerobic exercises have been shown to benefit those with fibromyalgia. A successful method to reintroduce exercise is through incremental steps.

Starting with manageable amounts, such as a 10-minute walk thrice weekly, helps muscles gradually adapt to regular activity. Tying these exercises to practical goals, like walking kids to school, adds significance and encourages routine implementation. Distributing exercise in short durations throughout the week prevents the pattern of infrequent, intense activity followed by extended periods of increased pain and fatigue.

Activity Structuring

Activity structuring involves setting small, achievable daily goals to adapt to the limitations of pain and fatigue while maintaining functionality. Often, patients overexert themselves on days when symptoms are less severe, leading to a cycle of overactivity followed by days of incapacitation. Breaking this pattern is crucial. By organizing and prioritizing tasks, like cleaning one room per day instead of the entire house, patients can stay active without intensifying their symptoms.

Psychological Therapy

Psychological treatments, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, mindfulness practices, relaxation techniques, and biofeedback, are employed in managing fibromyalgia. Cognitive-behavioral therapy works on altering thoughts and behaviors to change emotional responses to pain, enhancing control and function. For instance, reassurance about the benefits and safety of exercise can shift patients' perceptions and increase their willingness to engage in physical activity.

Mindfulness-based strategies, including relaxation and stress management, emphasize accepting the condition and understanding the impact of emotions on coping. Recognizing how focusing on pain can impair daily activities is a step towards setting practical goals (like walking to the store) to regain control over the condition.

Sleep Management

Sleep disturbances are frequently reported by fibromyalgia patients. Addressing this through behavioral strategies (see Table 2) and potentially supplementing with medications like amitriptyline and duloxetine can be beneficial.

| Table 2: Behavioral Strategies |

|---|

| • Develop a sleep routine that involves going to bed and getting up at a set time |

| • Avoid daytime sleeping |

| • Reduce intake of stimulants such as coffee and alcohol |

| • Exercise early in the day and not in the evening |

| • Increase the amount of exercise taken during the day |

| • Avoid watching television in the bedroom |

| • Ensure the bedroom is well ventilated |

| • Have a hot bath as part of a sleep routine |

Non-Traditional Therapies

Inquiries about non-conventional treatments are common among patients, though definitive evidence in this field is scarce. Practices such as Tai chi, yoga, and meditation have demonstrated benefits in reducing muscle stiffness, stress, depression, anxiety, and in enhancing self-esteem. Acupuncture has also been linked to a minor decrease in pain for those with FMS.

Pharmacological Management

Fibromyalgia patients often experience a range of symptoms, leading to the prescription of various drugs. It’s important to discontinue any medication that proves ineffective after a reasonable trial period, as it’s not uncommon to find patients taking multiple ineffective drugs. Pain relief might be sought through medications like paracetamol or co-codamol, though strong opioids have limited supporting evidence. The effectiveness of other drugs has been established in clinical trials, as detailed in Table 3. Selecting the appropriate medication should be a personalized decision, considering the patient’s primary symptoms, other health conditions, and personal preferences.

| Table 3: Drug treatment |

|---|

| * Amitriptyline (10–50 mg): on sleep and pain |

| * Duloxetine (30–60 mg): on sleep, pain and mood |

| * Pregabalin (150–450 mg) and gabapentin (1200–2400 mg): on pain, sleep and quality of life |

| * Fluoxetine (20–60 mg): on pain, fatigue, depression, sleep and quality of life |

Final Thoughts

Conditions like fibromyalgia, characterized by chronic widespread pain, fatigue, disturbed sleep, and various somatic complaints, are diagnosed based on clinical assessment and exclusion of other causes through medical tests. An integrated, multidisciplinary approach is essential in managing these conditions, aiming to improve the patient’s physical, mental, and social well-being.

Share

Tags

Counters