Decoding Osteoarthritis: A Modern Perspective on Joint Health and Disease Progression

Posted on January 31, 2024 • 11 minutes • 2154 words • Other languages: Русский

Table of contents

Osteoarthritis (OA), the most prevalent disorder impacting synovial joints , stands as a primary source of movement-related disabilities and poses a significant challenge to health services. It was once considered merely a result of wear and tear due to age and injury. However, current understanding portrays OA as a dynamic phenomenon involving damage to joint tissues and the body’s efforts to repair these tissues. This condition can arise from abnormal stress on a healthy joint or typical stress on a compromised joint. In many instances, a combination of these factors is at play. Thus, OA emerges from a complex interplay of various processes and risk factors. The significance of these risk factors can vary depending on the joint, and the factors influencing the onset of OA may be different from those affecting its progression. While natural joint repair mechanisms often counterbalance initial damage, leading to OA without symptoms, there are cases where these mechanisms fail, resulting in symptomatic OA accompanied by pain and loss of function.

Classification and Origins

Osteoarthritis is typically categorized into two types: primary and secondary. Primary OA often affects specific joints and is primarily attributed to genetic factors and inherent susceptibilities.

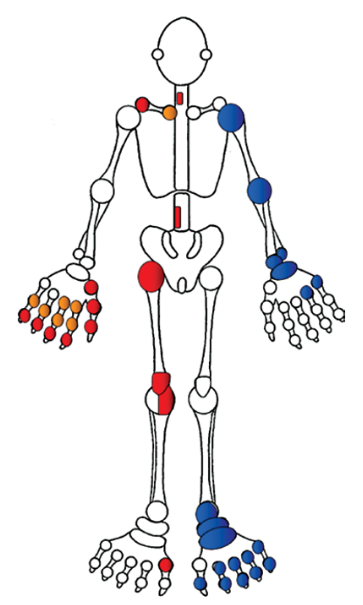

| Joints involvement in OA. Most commons: red, less common: yellow, least common: blue |

|---|

|

A notable indicator of primary OA is the development of multiple Heberden’s nodes (characterized by the bony enlargement of the hand’s distal interphalangeal joints) in middle age, which is a strong predictor for knee OA and other prevalent forms of OA (referred to as nodal generalized OA).

| Heberden’s nodes |

|---|

|

Nevertheless, OA has the potential to impact any synovial joint. The manifestation of OA in less common joints, like the ankle, should prompt an evaluation for secondary OA. Causes of secondary OA often include past joint injuries, fractures, or inflammatory conditions such as gout . Joint trauma is a frequent precursor, potentially leading to OA 15-20 years post-injury. This is a typical cause of early-onset OA that affects one or a few joints. The severity of OA is exacerbated when abnormal joint stress combines with pre-existing joint abnormalities. For instance, patients with hand OA (indicative of a genetic inclination towards OA) who suffer significant knee meniscal injuries are more likely to develop knee OA later on, as compared to those without hand OA.

Manifestations of Osteoarthritis

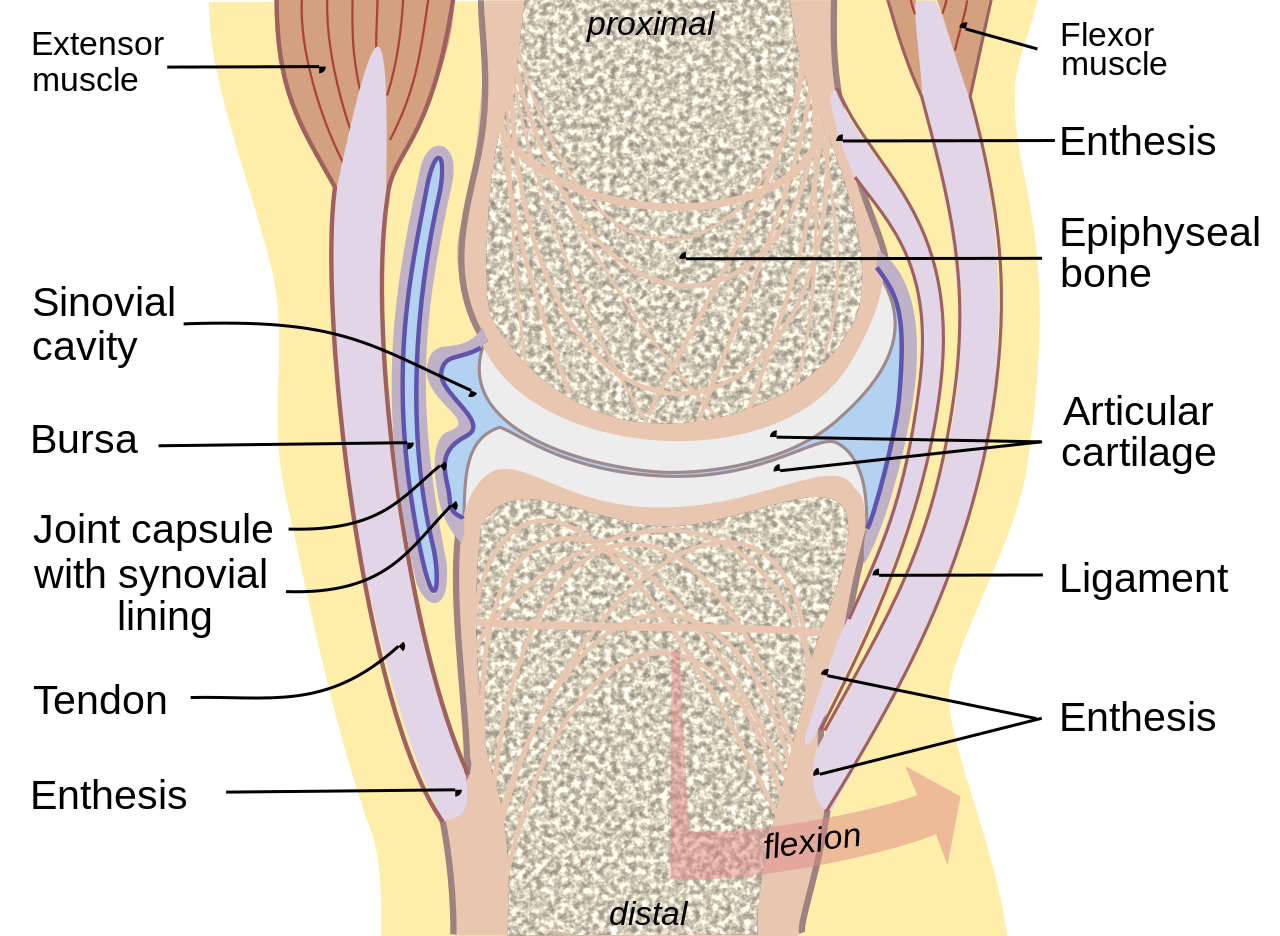

Key indicators of Osteoarthritis (OA) are discomfort, joint stiffness, and a diminished ability to move the affected joints. The pain associated with OA doesn’t originate from the hyaline cartilage , which lacks nerve supply, but rather from pain-sensing nerves and pressure-sensitive receptors located in surrounding joint structures like the synovium , joint capsule , the bone beneath the cartilage, and adjacent areas including ligaments and bursae .

| Joint: joint bursa, cartilage, sinovial cavity, tendon |

|---|

|

| Articular ligament |

|---|

|

The development of OA pain is gradual and typically impacts only one or a few joints at a time, worsening with joint use. Severe cases of OA may also lead to pain during the night. OA pain typically evolves in stages that may overlap:

- Initial Stage: Sharp, activity-induced pain, often triggered by physical strain, restricting high-impact activities with minimal impact on general functioning.

- Intermediate Stage: Persistent pain that interferes with everyday tasks.

- Advanced Stage: Continuous, dull or aching pain, interspersed with sporadic, intense flare-ups that significantly restrict mobility and daily functions.

In the initial stages of Osteoarthritis (OA), individuals often experience stiffness that lasts less than 30 minutes in the morning, as well as stiffness after brief periods of inactivity, commonly referred to as ‘gelling.’ These symptoms typically alleviate with movement of the affected joints. The stiffness in OA is partly due to the build-up of hyaluronan (a key component of synovial fluid acting as a lubricant) and its fragments within the deeper layers of the arthritic synovium during periods of rest, leading to a reduction of water content in the synovial tissues. Movement aids in the redistribution of hyaluronan to the lymphatic system and bloodstream, resulting in rehydration of the synovial tissue and a reduction in joint stiffness.

Additional symptoms of OA, such as movement limitations, functional impairment, and disability, vary depending on the affected joint’s location and severity, as well as the individual’s lifestyle and activities. Changes in the cartilage matrix in OA can lead to the accumulation of various types of crystals like calcium pyrophosphate, basic calcium phosphate, and monosodium urate, potentially causing episodes of acute crystal-induced synovitis.

Clinical Assessment of Osteoarthritis

During a physical examination, several indicative signs of Osteoarthritis (OA) are often observed. These include bony enlargements, localized soreness, a grating sensation or noise called crepitus, limited joint mobility, and signs of joint deformity or instability. The bony enlargements are primarily due to the formation of osteophytes and changes in bone structure.

| Osteophytes are bony projections that form along joint margins. |

|---|

|

Pain localized along the joint line typically indicates problems within the joint, whereas pain outside this area often points to issues with surrounding tissues, a consequence of changed joint mechanics.

Crepitus is experienced as a gritty sensation or sound, resulting from the interaction of damaged cartilage or bones, noticeable during both voluntary and involuntary movements. The restriction in both active and passive movements in OA is largely attributed to bone spurs, thickening of the joint capsule, and changes in the synovial membrane, sometimes accompanied by fluid accumulation. Muscle atrophy and weakness are usually indicative of advanced OA. Deformity and joint instability are signs of significant joint damage. Notably, pronounced inflammation is not characteristic of OA. Any signs of redness, acute pain, swelling, or warmth may indicate the presence of crystal-induced synovitis.

In comparison, Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) typically affects multiple small and large joints simultaneously and symmetrically. It’s important to recognize that coexisting conditions such as fibromyalgia, sleep issues, anxiety, depression, and negative social factors can influence the symptoms and treatment outcomes in OA. Therefore, a thorough evaluation of patients should include assessments to identify these additional factors.

Diagnostic Approach to Osteoarthritis

The diagnosis of Osteoarthritis typically relies on clinical evaluation, especially when characteristic symptoms and signs are present in individuals within the higher risk age bracket. This approach is often sufficient, as there’s a noted weak link between the severity of symptoms and structural changes in the joints. While imaging techniques like ultrasound can detect joint effusion, thickening of the synovial membrane, and minor power Doppler signals in OA-affected joints, these findings are considerably less pronounced than in cases of inflammatory joint diseases. The analysis of synovial fluid is generally recommended only when there’s a suspicion of concurrent crystal-related disorders or infection.

Handling Osteoarthritis

Effective management of Osteoarthritis focuses on educating patients, alleviating discomfort, enhancing daily functioning, and slowing the disease’s progression. A tailored approach to treatment is crucial, taking into account individual preferences, the specific joints affected, OA risk factors, the extent of structural damage, pain intensity, and the impact on the patient’s daily activities. Given that OA symptoms tend to fluctuate, it is beneficial to equip patients with a variety of treatment strategies to manage both the less active phases and the flare-ups of the condition.

Educating Patients and Ensuring Information Accessibility

Providing education and information is not just a professional duty but also an integral part of treatment that can positively impact outcomes. Dispelling the misconception that Osteoarthritis is merely an age-related degeneration of joints is crucial, as this belief often leads to unnecessary reductions in physical activity. The importance of weight management should also be emphasized in patient education. There is strong evidence supporting the effectiveness of educational programs in helping patients understand OA and adopt self-management techniques.

Implementing an Exercise Regimen

It is essential for individuals with OA to engage in a personalized daily exercise routine. This should encompass sustained isometric exercises, aerobic activities, and supplementary stretching or range of motion exercises. Aerobic exercises are known to reduce pain and disability associated with OA, enhance overall well-being and sleep quality, and are advantageous for managing common coexisting conditions. Physical activity and exercise can be varied, ranging from home-based routines to group classes. Water-based exercises, where patients experience only a fraction of their body weight, are particularly beneficial. They reduce the strain on joints caused by obesity and enable free joint movement and aerobic training, especially for those with OA in the lower extremities.

Mitigating Negative Biomechanical Impacts

Adjusting the approach to physically demanding tasks, like household chores or gardening, can significantly benefit individuals with OA. Spreading these activities throughout the day and incorporating breaks, a strategy known as ‘pacing,’ helps in reducing prolonged mechanical stress on the joints. Weight loss is particularly effective for overweight and obese patients, as it not only improves mobility and reduces pain but also decelerates the progression of knee OA. Selecting the right footwear—featuring a thick, soft sole, low heel, wide front, and cushioned upper—can lessen the impact on the joints for those with knee and hip OA. The use of a cane in the hand opposite the affected joint and other mobility aids can decrease the stress across affected joints. Specific devices like wedged insoles and splints for the base of the thumb are beneficial for managing knee OA and trapeziometacarpal OA, respectively. Other adaptations, such as elevated seating, stair handrails, walk-in showers, and car modifications, can also assist in alleviating symptoms.

Pharmacological Approaches in Osteoarthritis Management

When treating OA, the presence of cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and renal conditions, among other comorbidities, plays a crucial role in determining the choice of supplementary drug treatments. Pain management is a primary concern for patients. The initial pharmacological intervention typically includes Paracetamol or topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). For knee or hand OA, topical NSAIDs are often favored over Paracetamol due to their minimal systemic side effects and superior pain relief.

If topical NSAIDs and/or Paracetamol prove insufficient, oral NSAIDs, selective COX-2 inhibitors, and weak opioids such as codeine or tramadol may be considered. To mitigate the risk of gastrointestinal issues like bleeding and ulcers associated with NSAIDs, co-prescription of proton pump inhibitors is recommended. While selective COX-2 inhibitors are gentler on the gastrointestinal tract, they, along with some traditional NSAIDs, elevate cardiovascular risks. Traditional NSAIDs may also impair renal function, particularly in older adults. Therefore, NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors should be prescribed at the lowest effective dose and used as needed. Although weak opioids can effectively alleviate pain, side effects like headaches, confusion, and constipation often limit their use.

Studies have indicated that glucosamine and chondroitin sulphates may slow the progression of joint space narrowing in OA, but there are also studies with negative results. Cisequently, they are not recommended by NICE (2008) guidelines.

Intra-articular corticosteroid injections provide rapid and effective pain relief lasting from weeks to months. They are particularly beneficial for managing pain during critical personal occasions or when initiating other treatments like exercise programs. Hyaluronan injections, either as a single dose or a series over 3-5 weeks, are another option, but their effectiveness is variable, and they are not widely recommended due to cost and logistical issues, as per NICE (2008) guidelines.

Surgical Interventions in Osteoarthritis

Total joint replacement (TJR) has significantly enhanced the treatment of advanced knee or hip Osteoarthritis. Surgical procedures are also employed in managing late-stage OA of the shoulder, elbow, and base of the thumb. While there’s no universal consensus on when to refer a patient for TJR, common criteria include persistent, unmanageable pain and significant functional impairment despite exhaustive conservative treatments. Age alone does not exclude a patient from being a candidate for surgery. Additionally, surgical procedures aimed at correcting anatomical issues that predispose individuals to knee and hip OA, such as tibial osteotomy or hip labral repair, can be effective in preventing the progression of the disease.

Summary

To conclude, Osteoarthritis (OA) is a progressively common condition that, despite frequently being symptom-free, can lead to varying degrees of discomfort and disability. Adopting a personalized and comprehensive management strategy is crucial in effectively alleviating pain, reducing disability, and enhancing the quality of life for those affected. The cornerstone of managing OA lies predominantly in non-pharmacological approaches.

References

- The effect of Fu’s subcutaneous needling in treating knee osteoarthritis patients: A randomized controlled trial

- Multiple joint osteoarthritis (MJOA): What’s in a name?

- Genicular artery embolization for knee osteoarthritis: Results of the LipioJoint-1 trial

- Exosomes derived from mesenchymal stem cells rescue cartilage injury in osteoarthritis through Ferroptosis by GOT1/CCR2 expression

- Methotrexate to treat hand osteoarthritis with synovitis (METHODS): an Australian, multisite, parallel-group, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial

- Recent targets of osteoarthritis research

- Joint pressure stimuli increase quadriceps strength and neuromuscular activity in patients with knee osteoarthritis

- Injection of intra-articular sodium hyaluronidate (Sinovial®) into the carpometacarpal joint of the thumb (CMC1) in osteoarthritis. A prospective evaluation of efficacy

- Different molecular weights of hyaluronan research in knee osteoarthritis: A state-of-the-art review

- Intra-articular hyaluronic acid in knee osteoarthritis: clinical data for a product family (ARTHRUM), with comparative meta-analyses

- Viscosupplementation for Hip Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Efficacy on Pain and Disability, and the Occurrence of Adverse Events

Share

Tags

Counters