Select non-duplicates: SQL interview question

Posted on September 9, 2024 • 7 minutes • 1465 words

Table of contents

Task definition

We define the following schema:

CREATE TABLE dup(id SERIAL PRIMARY KEY, email TEXT NOT NULL, phone NOT NULL);

Duplicate rows are defined as two or more rows which have the same email OR phone columns.

Our task is to write SQL which selects rows which have no duplicates initially and also any single row which represents a group of duplicates.

Solution

Naive solution

The straigtforward and incorrect approach is to apply DISTINCT serially. For example:

INSERT INTO dup(email, phone) VALUES('a','1'),('a','2'), ('b','2'), ('c','1'), ('d', '3')

| id | phone | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | a | 1 |

| 2 | a | 2 |

| 3 | b | 2 |

| 4 | c | 1 |

| 5 | d | 3 |

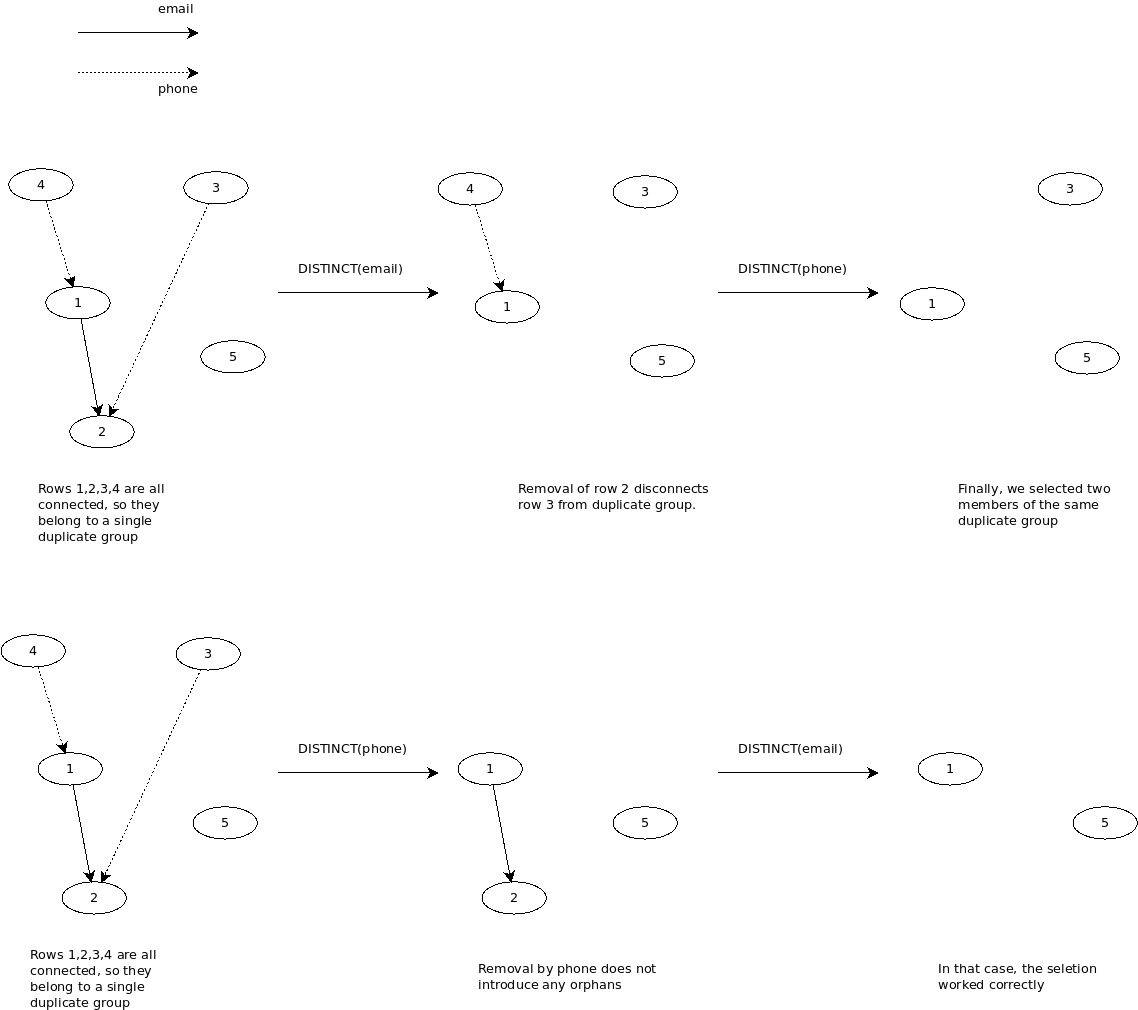

In that table, row 1 is a duplicate of row 4 because of the same phone, row 1 is also a duplicate of row 2 because of the same email, row 3 is a duplicate of row 2 because of the same phone. Thus, the rows 1-4 are are duplicates. The required result of our selection is any row of duplicates group of rows 1-4 and row 5 which has no duplicates.

Let’s select:

SELECT DISTINCT ON(phone) * FROM

(SELECT DISTINCT ON(email) * FROM dup) AS q;

Select on distinct email produces:

| id | phone | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | a | 1 |

| 3 | b | 2 |

| 4 | c | 1 |

| 5 | d | 3 |

Next select on distinct phone produces:

| id | phone | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | a | 1 |

| 3 | b | 2 |

| 5 | d | 3 |

We see that we selected row 1 and 3 although they belong to the same duplicate group.

The change of order of selection does help in that case:

SELECT DISTINCT ON(email) * FROM

(SELECT DISTINCT ON(phone) * FROM dup) AS q;

Select on distinct phone produces:

| id | phone | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | a | 1 |

| 2 | a | 2 |

| 5 | d | 3 |

Next select on distinct email produces:

| id | phone | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | a | 1 |

| 5 | d | 3 |

The correct result was due to a way the duplicates were connected. The following diagram makes this clear.

We can see that any kind of graph can exist which will fail the naive selection method we use.

Recursive CTE query

The correct and recursive solution is the following query.

WITH RECURSIVE connected_groups AS (

-- Base case: each row starts as its own group

SELECT

id,

email,

phone,

id AS group_id

FROM dup

UNION

-- Recursive case: find connections via email or phone

SELECT

d.id,

d.email,

d.phone,

cg.group_id

FROM dup d JOIN connected_groups cg

ON d.email = cg.email OR d.phone = cg.phone

WHERE d.id <> cg.id

),

min_group AS (

-- Find the smallest group_id for each row's group

SELECT

cg.id,

MIN(cg.group_id) AS group_id

FROM connected_groups cg

GROUP BY

cg.id

)

SELECT d.* FROM dup d

JOIN

min_group mg

ON d.id = mg.id

JOIN (

-- Select one row per group (e.g., the row with the smallest id)

SELECT

mg.group_id,

MIN(mg.id) AS min_id

FROM min_group mg

GROUP BY

mg.group_id

) grp

ON mg.group_id = grp.group_id AND mg.id = grp.min_id;

Let’s examine several cases with that solution.

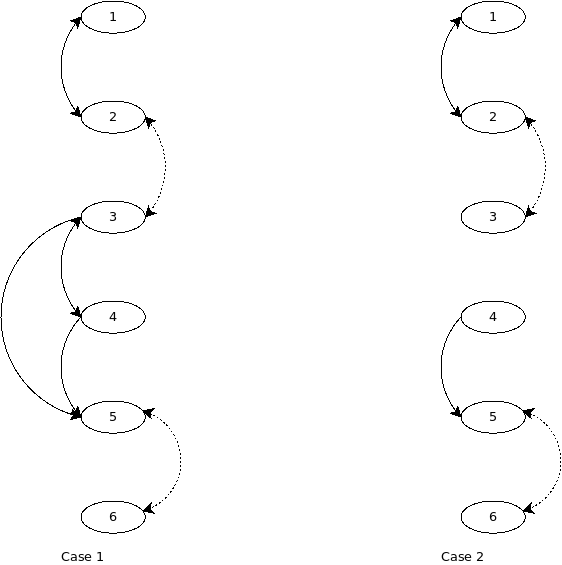

Case 1

| id | phone | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | a | 1 | |

| 2 | a | 2 | |

| 3 | b | 2 | |

| 4 | a | 3 | |

| 5 | a | 4 | |

| 6 | c | 4 |

TRUNCATE dup RESTART IDENTITY;

INSERT INTO dup(email,phone) VALUES

('a','1'),

('a','2'),

('b','2'),

('a','3'),

('a','4'),

('c','4');

The result of the query:

id | email | phone

----+-------+-------

1 | a | 1

(1 row)

So, it’s ok.

Case 2

| id | phone | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | a | 1 |

| 2 | a | 2 |

| 3 | b | 2 |

| 4 | c | 4 |

| 5 | c | 5 |

| 6 | d | 5 |

TRUNCATE dup RESTART IDENTITY;

INSERT INTO dup(email,phone) VALUES

('a','1'),

('a','2'),

('b','2'),

('c','4'),

('c','5'),

('d','5');

The result of the query:

id | email | phone

----+-------+-------

4 | c | 4

1 | a | 1

This works nice, too.

Non-recursive solution

The recursive solution turns out to be very slow. On amazon RDS instance with 32GB RAM and 4 vCPU, execution time was 2125961.136 ms for 100,000 rows.

To find duplcaites we decided to use out-of-db filtering.

Step 1: grouping ids of the same email or phone

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS email_group(id SERIAL PRIMARY KEY, email TEXT NOT NULL, ids INTEGER[]);

INSERT INTO email_group(email, ids)

SELECT DISTINCT ON(email) email, ARRAY_AGG(id)

FROM dup GROUP BY email;

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS phone_group(id SERIAL PRIMARY KEY, phone TEXT NOT NULL, ids INTEGER[]);

INSERT INTO phone_group(phone, ids)

SELECT DISTINCT ON(phone) phone, ARRAY_AGG(id)

FROM dup GROUP BY phone;

Let’s see an example:

SELECT * FROM dup;

id | email | phone

----+-------+-------

1 | a | 1

2 | a | 2

3 | b | 2

4 | a | 3

5 | a | 4

6 | c | 4

(6 rows)

SELECT * FROM email_group;

id | email | ids

----+-------+-----------

1 | a | {1,2,4,5}

2 | b | {3}

3 | c | {6}

(3 rows)

SELECT * FROM phone_group;

id | phone | ids

----+-------+-------

1 | 1 | {1}

2 | 2 | {2,3}

3 | 3 | {4}

4 | 4 | {5,6}

(4 rows)

Step 2: Union-find algorithm (aka disjoint set algorithm)

Correctness

The algorithm works as follows (group 1 = email_group and group 2 = phone group below):

- Input: You have two groups of sets (in this case,

group 1andgroup 2). - Union: For each set in

group 1, you check if it has any intersection with any sets ingroup 2. If they intersect, you merge (union) them into a single set. - Skipping Duplicates: After merging sets, you skip any set in

group 1that has already been processed and merged with other sets.

This algorithm is general enough for identifying and merging overlapping sets because:

- Union Property: The union operation is commutative and associative. This means that the order in which you process the sets does not affect the final outcome. As long as you consider all sets and merge them when they overlap, the result will be the same.

- Transitive Closure: The merging (union) operation will combine all interconnected sets into a single larger set, preserving the transitive property. For example, if set A intersects with set B, and set B intersects with set C, all three sets will be merged into a single set containing elements from A, B, and C.

By following the process for all sets in both groups, you ensure that all overlapping and interconnected sets are merged into distinct groups, effectively identifying the “duplicate” sets. Therefore, the procedure is general enough for finding duplicates in any collection of sets.

Implementation

class UnionFind {

constructor(size) {

this.parent = Array.from({ length: size }, (_, i) => i);

this.rank = Array(size).fill(1);

}

find(x) {

if (this.parent[x] !== x) {

this.parent[x] = this.find(this.parent[x]); // Path compression

}

return this.parent[x];

}

union(x, y) {

let rootX = this.find(x);

let rootY = this.find(y);

if (rootX !== rootY) {

// Union by rank

if (this.rank[rootX] > this.rank[rootY]) {

this.parent[rootY] = rootX;

} else if (this.rank[rootX] < this.rank[rootY]) {

this.parent[rootX] = rootY;

} else {

this.parent[rootY] = rootX;

this.rank[rootX] += 1;

}

}

}

}

function findDuplicates(groups) {

const elementToIndex = {};

let nextIndex = 0;

let processedElements = 0;

// Assign a unique index to every unique element across all groups

console.log(`Assigning unique indices to elements in ${groups.length} groups...`);

for (let group of groups) {

for (let element of group) {

if (!(element in elementToIndex)) { // Check existence in the object

elementToIndex[element] = nextIndex++;

}

}

// Log progress for every 100,000 groups processed

processedElements++;

if (processedElements % 100000 === 0) {

console.log(`Processed ${processedElements} groups for unique indexing...`);

}

}

console.log(`Finished assigning indices. Total unique elements: ${nextIndex}`);

// Initialize union-find data structure

const uf = new UnionFind(nextIndex);

// Union elements within each group

console.log(`Performing union operations for ${groups.length} groups...`);

processedElements = 0;

for (let group of groups) {

for (let i = 1; i < group.length; i++) {

uf.union(elementToIndex[group[0]], elementToIndex[group[i]]);

}

// Log progress for every 100,000 groups processed

processedElements++;

if (processedElements % 100000 === 0) {

console.log(`Performed union operations for ${processedElements} groups...`);

}

}

console.log(`Finished union operations.`);

// Find unique sets

console.log(`Finding unique sets...`);

const rootToGroup = {};

let elementCount = 0;

for (let element in elementToIndex) {

let root = uf.find(elementToIndex[element]);

if (!(root in rootToGroup)) {

rootToGroup[root] = [];

}

rootToGroup[root].push(element);

// Log progress for every 100,000 elements processed

elementCount++;

if (elementCount % 100000 === 0) {

console.log(`Processed ${elementCount} elements for unique sets...`);

}

}

console.log(`Finished finding unique sets. Total unique groups: ${Object.keys(rootToGroup).length}`);

// Collect results

return Object.values(rootToGroup);

}

async function main() {

const group1 = [[1,2,3],[2]];

const group2 = [[4,5], [1,3]];

console.log(`group1 size: ${group1.length}, group2 size: ${group2.length}`);

// Combine all groups into one

console.log('Starting to find duplicates...');

const mergedGroups = findDuplicates([...group1, ...group2]);

await fs.writeFile("duplicates.json", JSON.stringify(mergedGroups, null, 2), {encoding: "utf8"});

let cnt = 0;

for (const a of mergedGroups) {

if (a.length > 1) {

cnt++;

}

}

console.log(`Number of found duplicate groups: ${cnt}`);

pool.end();

}

main();

This algorithm is fast enough to process millions of groups in minutes.

Share

Tags

Counters