Predators to Partners: The Evolutionary Saga of Eukaryotes and Their Symbiotic Ascent

Posted on February 2, 2024 • 24 minutes • 4953 words

Table of contents

- The Evolutionary Path to Eukaryotic Complexity

- The Symbiotic Origins of Complex Cells

-

Questions and Answers on evolution of Eukaryotes, Mitochondria and Chloroplasts

- Question: According to the endosymbiosis theory, what are the origins of the inner and outer membranes of mitochondria?

- Question: Given that bacteria are characterized by having both inner and outer membranes, should mitochondria, derived from such bacterial ancestors, not exhibit a structure consisting of three membranes?

- Question: What are the specific proteins and molecular features present in mitochondrial membranes that indicate their bacterial origins?

- Question: What feature was not present in the first eukaryotes?

- Question: What made the first eukaryotes to be different from bacteria or archae?

- Question: What are the advantages and disadvantages of linear chromosomes compared to circular ones?

- Question: What synapomorphy defines the eukarya?

- Question: What benefits does the nucleus offer to eukaryotic cells, and what evolutionary pressures led to its development?

- Question: Why have prokaryotes continued to thrive and exist alongside eukaryotes, despite the evolutionary advantages provided by the eukaryotic nucleus?

- Question: Why did eukaryotes evolve from prokaryotes, and what drove the development of increased complexity in eukaryotes, given the success and adaptability of prokaryotes?

The Evolutionary Path to Eukaryotic Complexity

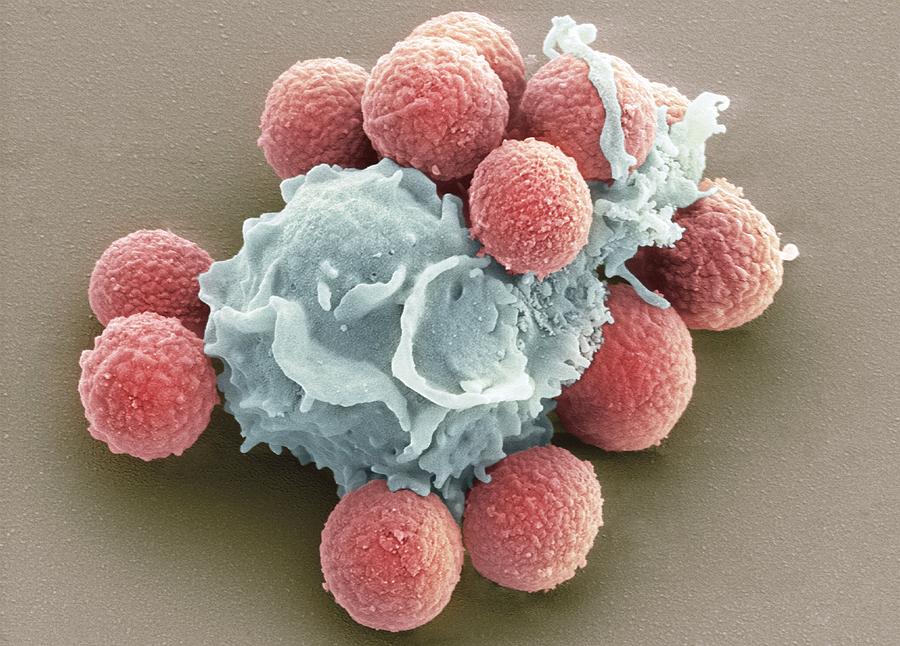

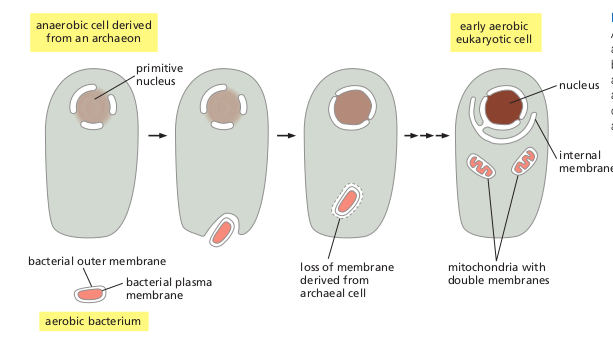

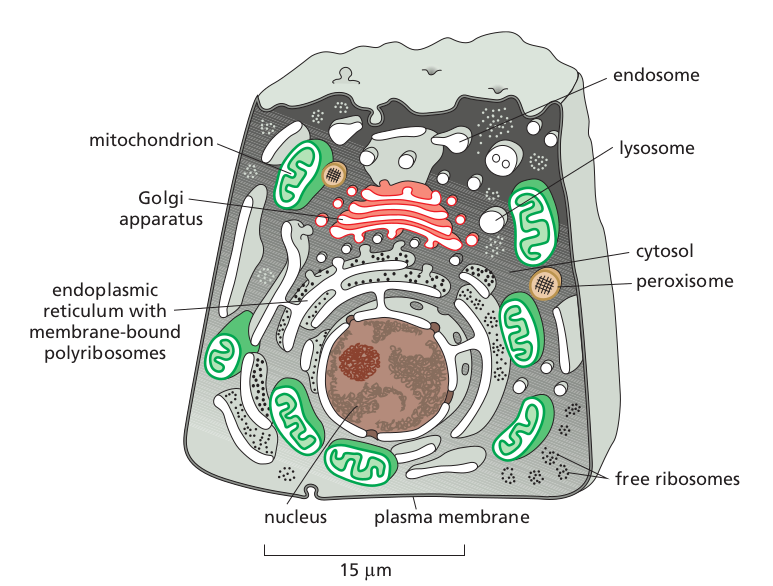

Eukaryotic cells distinguish themselves through a unique structural organization, housing their genetic material within a nucleus encased by a nuclear envelope, a dual-layered membrane that delineates DNA from the cytoplasm. Unlike their prokaryotic counterparts, eukaryotic cells are significantly larger, often by tenfold in linear dimensions and a thousandfold in volume. They feature a sophisticated cytoskeleton composed of protein filaments that interlace the cytoplasm, supporting the cell’s structure, determining its shape, and facilitating movement with a network of structural proteins, acting as cellular scaffolds and motors. Beyond the nuclear envelope, eukaryotes possess a complex series of internal membranes akin to the plasma membrane, which form various compartments within the cell involved in processes such as digestion and secretion. Without the rigid cell walls found in many bacteria, animal cells and certain autonomous eukaryotic cells, known as protozoa, have the remarkable ability to swiftly alter their form and engulf other cells or particles through the process of phagocytosis.

| The major features of eukaryotic cells |

|---|

|

The origins and developmental sequence of the distinctive features of eukaryotic cells remain largely unknown. Nonetheless, a credible theory suggests that these characteristics might stem from the lifestyle of an ancient predatory cell that survived by engulfing and consuming other cells. This predatory behavior necessitated a larger cell size and a malleable plasma membrane, supported by a complex cytoskeleton to facilitate movement. Additionally, the need to safeguard the cell’s lengthy, delicate DNA strands likely led to the evolution of a distinct nuclear area, isolating the genetic material from potential harm caused by cytoskeletal activities.

The Symbiotic Origins of Complex Cells

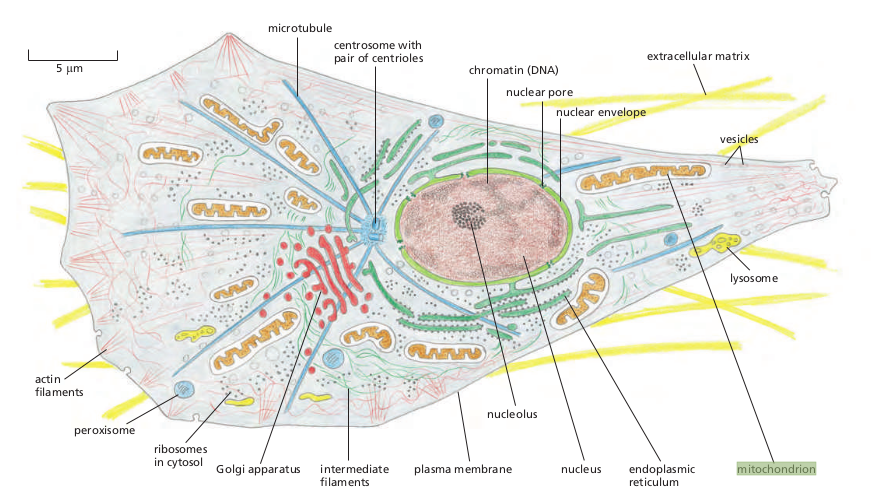

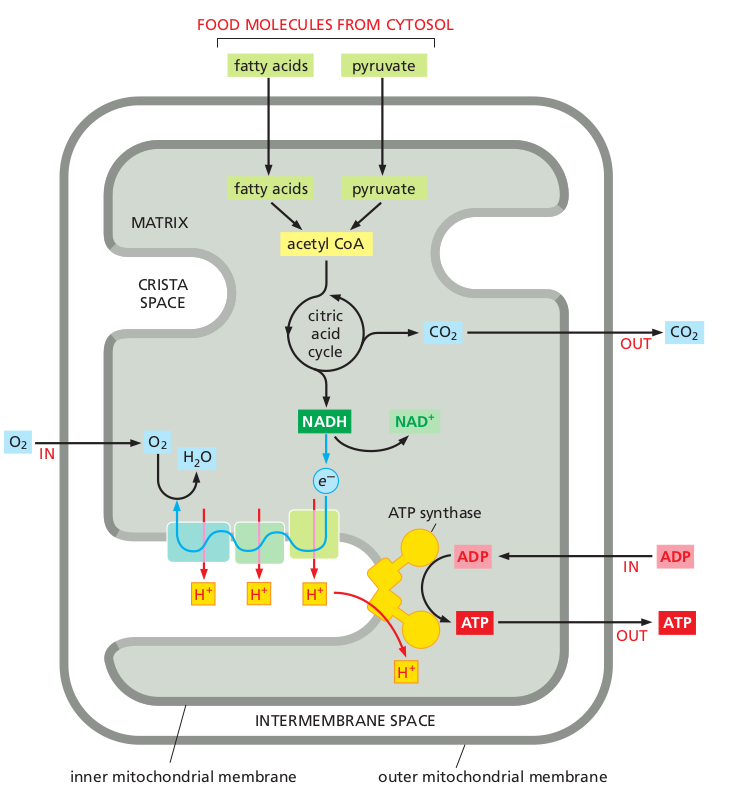

The predatory nature of early eukaryotic cells offers insight into a critical aspect of their biology: the presence of mitochondria. These organelles, crucial for cellular energy production through the oxidation of nutrients, are encased within a dual-membrane structure and possess their distinct DNA, ribosomes, and transfer RNAs, mirroring the characteristics of small bacteria.

The consensus among scientists is that mitochondria were once free-living aerobic bacteria that an ancestral anaerobic cell absorbed. These bacteria managed to avoid being digested, gradually forming a symbiotic relationship with their host cell, benefiting from protection and nutrients while supplying energy.

| Mitochndrion |

|---|

|

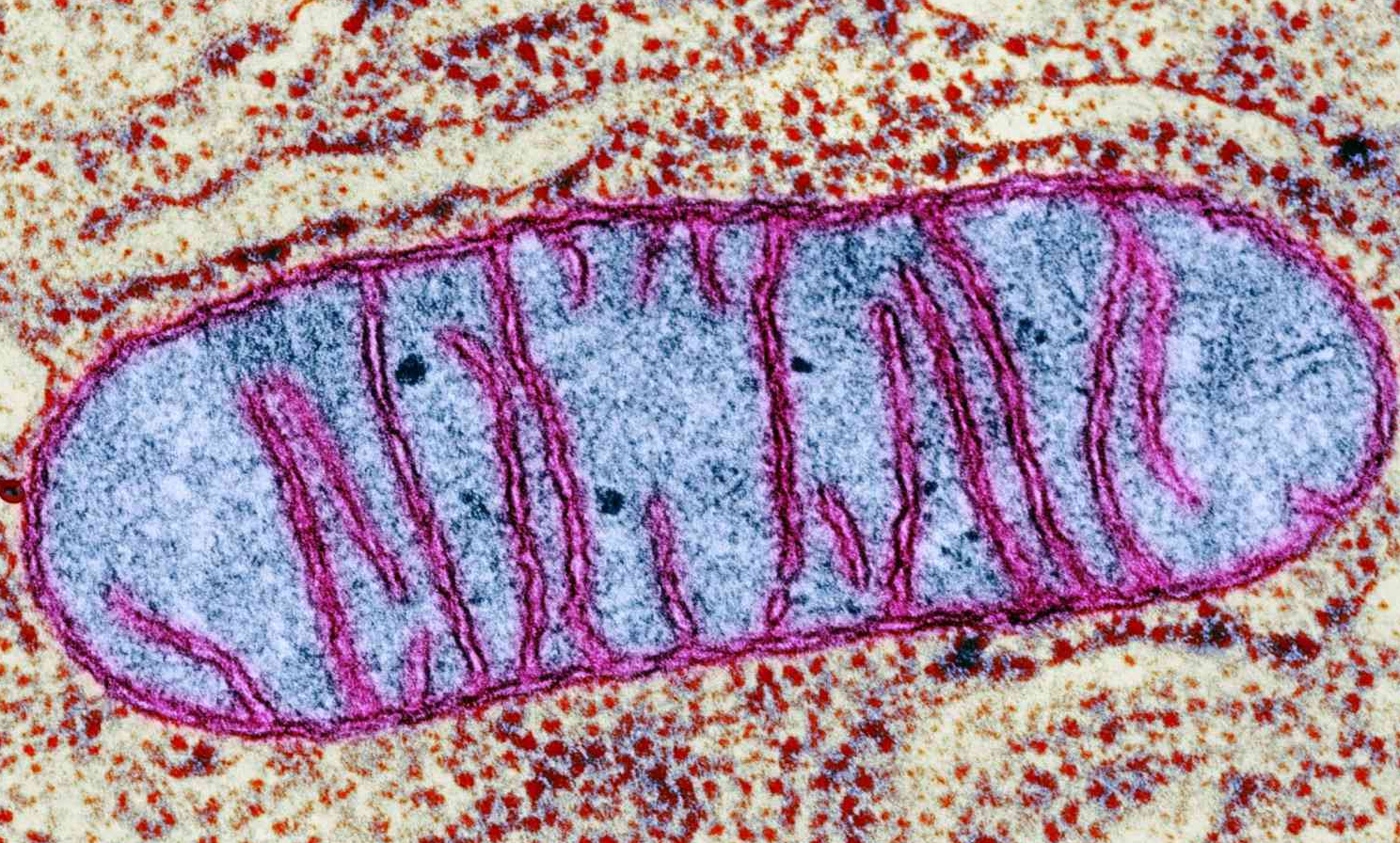

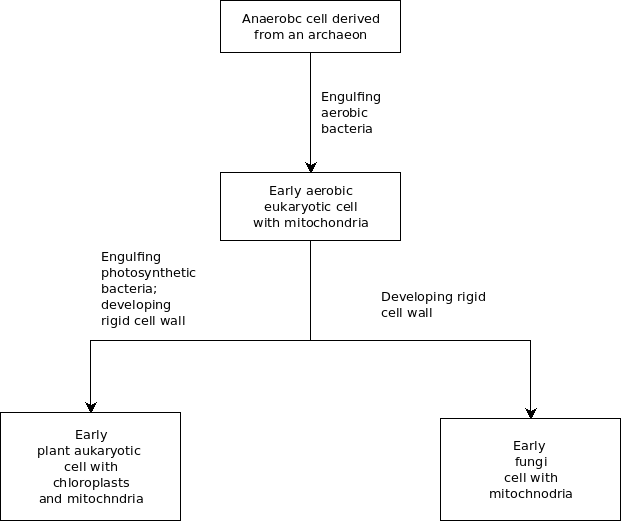

This symbiotic theory is supported by genomic studies suggesting that eukaryotic cells emerged when an archaeal host cell incorporated an aerobic bacterium. This event is pivotal, explaining why even anaerobic eukaryotic cells today bear mitochondrial traces, indicating a shared mitochondrial ancestry.

| The origin of mitochondria. |

|---|

|

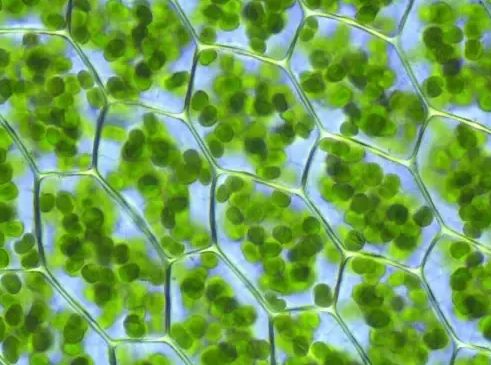

Beyond mitochondria, many eukaryotic cells, such as those in plants and algae, house chloroplasts—organelles responsible for photosynthesis. These too are believed to have originated from photosynthetic bacterial symbionts in cells already containing mitochondria, allowing these cells to produce their nutrients from sunlight, carbon dioxide, and water.

| Chloroplasts |

|---|

|

Cells with chloroplasts, like those in plants, have evolved beyond the need for predation, relying instead on the photosynthetic capabilities of their chloroplasts. This shift towards a farming lifestyle is evident in plant cells, which, despite having a cytoskeleton for movement, have lost the rapid shape-shifting and engulfing abilities in favor of developing a rigid, protective cell wall.

Fungi present a different evolutionary path, maintaining mitochondria without chloroplasts. Unlike animal cells and protozoa, fungi possess a rigid cell wall, restricting movement and ingestion of other cells. Instead of hunting, fungi have adopted a scavenging role, feeding on external nutrients released by other organisms or their decay, utilizing extracellular digestion facilitated by secreted enzymes.

| Animal (hunters) | Plants (farmers) | Fungi (scavengers) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Have mitochnodria | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Have chloroplasts | No | Yes | No |

| Have cell wall | No | Yes | Yes |

| Evolution |

|---|

|

Questions and Answers on evolution of Eukaryotes, Mitochondria and Chloroplasts

Question: According to the endosymbiosis theory, what are the origins of the inner and outer membranes of mitochondria?

The endosymbiosis theory, which explains the origin of mitochondria (and chloroplasts), suggests that these organelles originated from free-living prokaryotic organisms (specifically, bacteria) that were engulfed by early ancestral eukaryotic cells. According to this theory, the inner and outer membranes of mitochondria have distinct origins and roles, reflective of their evolutionary history:

-

Inner Membrane: The inner membrane of mitochondria is thought to be derived from the plasma membrane of the engulfed prokaryotic organism. This membrane contains proteins and enzymes essential for the electron transport chain and ATP synthesis, processes crucial for cellular respiration and energy production in eukaryotic cells. The presence of cardiolipin, a lipid unique to bacterial membranes and the inner mitochondrial membrane, supports this evolutionary linkage.

-

Outer Membrane: The outer membrane of mitochondria is believed to originate from the engulfing eukaryotic cell’s plasma membrane. When a free-living prokaryotic cell (the future mitochondrion) was engulfed, it became enclosed within a portion of the host cell’s plasma membrane. This event resulted in the formation of a double-membraned organelle, with the inner membrane coming from the engulfed bacterium and the outer membrane from the host cell.

This endosymbiotic event allowed the host cell to utilize the engulfed bacterium’s capabilities for energy production, leading to a symbiotic relationship. Over time, the engulfed prokaryotes evolved into modern mitochondria, transferring some of their genes to the host cell’s nucleus and losing much of their autonomy in the process. This theory is supported by several lines of evidence, including the similarities between mitochondria and bacteria in terms of DNA, ribosomes, and membrane structures.

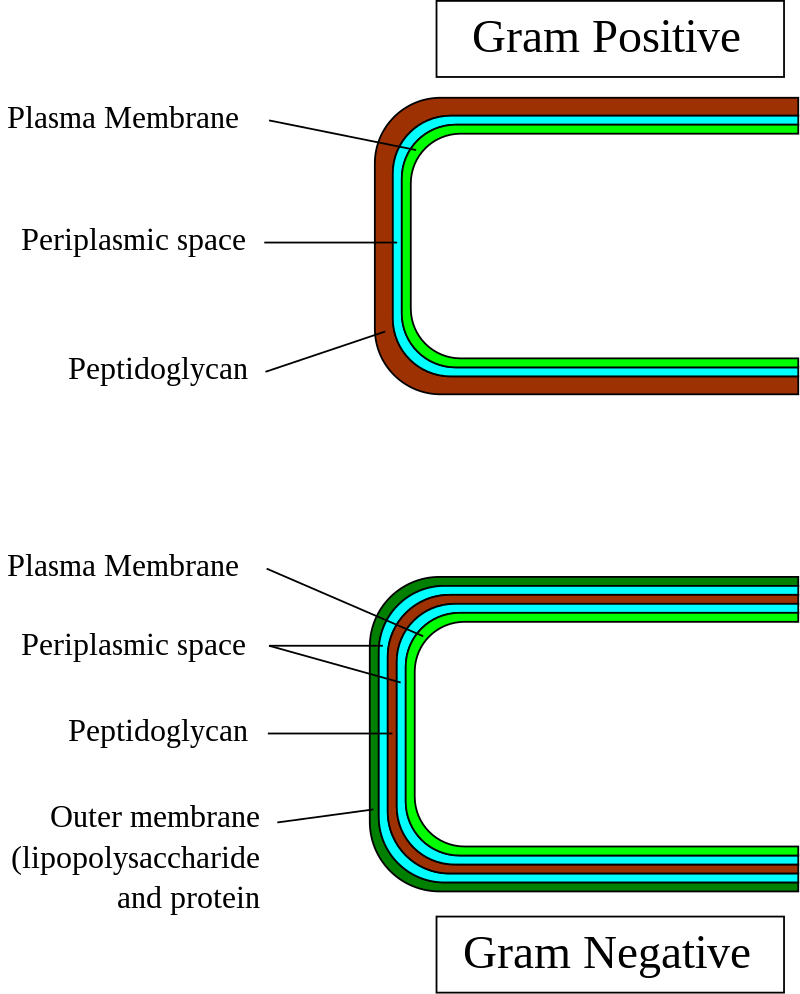

Question: Given that bacteria are characterized by having both inner and outer membranes, should mitochondria, derived from such bacterial ancestors, not exhibit a structure consisting of three membranes?

This question touches on an important aspect of the endosymbiosis theory and the general structure of bacteria. Indeed, many types of bacteria, especially Gram-negative bacteria , have both an inner (cytoplasmic) membrane and an outer membrane.

| Gram-negative and gram positive bacteria |

|---|

|

However, when it comes to mitochondria, the situation reflects a simplification that occurred during the endosymbiotic process.

-

Inner Membrane of Mitochondria: This corresponds to the original plasma membrane of the engulfed prokaryotic cell. It houses the machinery for ATP production, such as the electron transport chain and ATP synthase.

-

Outer Membrane of Mitochondria: This is derived from the host eukaryotic cell’s membrane that engulfed the bacterium, effectively becoming the outer boundary of the organelle. In the case of the engulfment process that led to mitochondria, the host cell’s phagocytic vesicle membrane (which enclosed the bacterium) became the mitochondrial outer membrane.

The discrepancy which was pointed out stems from the nature of the endosymbiotic event and the types of bacteria involved. The ancestral bacterium that gave rise to mitochondria is thought to have been similar to current alpha-proteobacteria , a group that includes both single-membrane and double-membrane species. However, the endosymbiotic theory posits that during the engulfment and subsequent evolutionary integration of this bacterium into the host eukaryotic cell, only a two-membrane system was retained for the mitochondrion: one from the bacterium itself and one from the host cell’s engulfing vesicle.

So, while it’s true that many bacteria have both inner and outer membranes, the structure of mitochondria does not directly translate to a three-membrane system because the outermost membrane of the engulfed bacterium was not retained as a distinct structure in the endosymbiotic process. Instead, the mitochondrial outer membrane is derived from the engulfing vesicle of the host cell, and the inner membrane is the original membrane of the engulfed bacterium, simplifying to a two-membrane organelle.

Question: What are the specific proteins and molecular features present in mitochondrial membranes that indicate their bacterial origins?

The evidence supporting the bacterial origin of mitochondria, including the composition of mitochondrial membranes, comes from several lines of comparison between mitochondria and bacteria, particularly proteobacteria from which mitochondria are thought to have descended. While there isn’t a single protein that serves as definitive proof, there are several features and proteins found in the mitochondrial membranes that highlight their bacterial heritage:

-

Cardiolipin: Cardiolipin is a distinctive phospholipid originally found in bacterial membranes, particularly in the inner membranes of bacteria. Its presence in the inner mitochondrial membrane is a strong indicator of mitochondrial ancestry from bacteria.

-

Electron Transport Chain (ETC) Components: Many of the proteins and complexes involved in the mitochondrial electron transport chain have homologs in bacteria. For example, Complexes I, III, IV, and V of the ETC share structural and functional similarities with their bacterial counterparts, supporting their evolutionary origin from bacteria.

-

ATP Synthase (Complex V): This complex is remarkably similar in both structure and function across all life forms, including bacteria and mitochondria, suggesting a common ancestral origin. Its mechanism of synthesizing ATP from ADP and inorganic phosphate mirrors that found in bacterial cells.

| Mitochondrion energy machine |

|---|

|

-

Transport Proteins: Various proteins responsible for the transport of ions and molecules across the mitochondrial membranes are similar to those found in bacterial membranes. This includes the TIM and TOM complexes (Translocase of the Inner/Outer Mitochondrial membrane) which are involved in the import of proteins into mitochondria, echoing bacterial protein import mechanisms.

-

Mitochondrial DNA: While not a protein, the circular nature of mitochondrial DNA , its gene structure, and the presence of genes that encode for membrane proteins resemble those found in bacteria. This genetic material encodes for some of the proteins found in the mitochondrial membranes, further linking mitochondria to their bacterial ancestors.

-

Ribosomes: Mitochondrial ribosomes (mitoribosomes) resemble bacterial ribosomes more than they do eukaryotic cytoplasmic ribosomes in terms of their sensitivity to antibiotics, size, and composition, indicating a bacterial origin. Mitoribosomes are responsible for synthesizing some of the membrane proteins encoded by mitochondrial DNA.

These features collectively support the hypothesis that mitochondria originated from an endosymbiotic event involving an ancestral eukaryotic cell and a proteobacterium. The conservation of these proteins and structures across mitochondria and bacteria is a testament to their shared evolutionary history.

Question: What feature was not present in the first eukaryotes?

The first eukaryotes likely lacked several features that are common in modern eukaryotic cells. One significant feature that was not present in the earliest eukaryotes is the fully developed endomembrane system, including the Golgi apparatus , endoplasmic reticulum (ER) , and lysosomes , which are involved in protein synthesis, modification, and transport, as well as waste processing.

While the ancestral eukaryote probably had precursors to these organelles, the complex, interconnected endomembrane system seen in modern eukaryotic cells would have evolved later as eukaryotic life diversified.

| Cell compartments |

|---|

|

Additionally, mitochondria and chloroplasts, the organelles responsible for cellular respiration and photosynthesis, respectively, are believed to have been acquired later through endosymbiotic events. The earliest eukaryotes may not have had these organelles. Instead, mitochondria are thought to have originated from the engulfment of an aerobic bacterium by a proto-eukaryotic cell, and chloroplasts from the subsequent engulfment of a photosynthetic bacterium by an early mitochondria-containing eukaryotic cell.

Another feature likely absent in the earliest eukaryotes is the complex cytoskeleton as seen in modern cells, with its dynamic system of microtubules, intermediate filaments, and actin filaments. While some form of structural support and intracellular transport mechanism might have been present, the sophisticated cytoskeletal machinery that plays critical roles in cell shape, division, and movement evolved over time.

Question: What made the first eukaryotes to be different from bacteria or archae?

Early eukaryotes, even before acquiring mitochondria through endosymbiotic events, differed from bacteria in several foundational aspects that set the stage for the complexity seen in modern eukaryotic cells. These differences are rooted in the structural and functional complexities that are inherent to eukaryotic cells, apart from the presence of mitochondria or chloroplasts. Key distinctions include:

-

Nuclear Envelope: One of the most fundamental differences is the presence of a nucleus enclosed by a nuclear envelope in eukaryotes, which compartmentalizes the genetic material, separating it from the cytoplasm. This feature allows for a more controlled and complex regulation of gene expression. Bacteria and archaea have their DNA in a nucleoid region without a surrounding membrane.

-

Cytoskeleton: Early eukaryotes possessed a cytoskeleton, an internal framework of protein filaments and tubules that provides structural support, enables cell movement, and plays crucial roles in intracellular transport and cell division. This complex cytoskeletal system is absent in bacteria and archaea, which have simpler mechanisms for maintaining cell shape and conducting cell division.

-

Size and Complexity: Eukaryotic cells are generally larger and have a more complex internal structure than prokaryotic cells. This increased size and complexity allow for a higher level of intracellular organization and the potential for specialization of cellular functions.

-

Endomembrane System: Even in the absence of mitochondria and chloroplasts, early eukaryotes likely had precursors to the endomembrane system, including structures analogous to the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus. These components are involved in the synthesis, folding, modification, and transport of proteins, distinguishing eukaryotic cells from prokaryotes in terms of their capabilities for protein processing and trafficking.

-

Genetic Material: Eukaryotic cells have their DNA organized into linear chromosomes within the nucleus, as opposed to the circular chromosomes found in bacteria and archaea. The association of eukaryotic DNA with histone proteins to form chromatin allows for an additional layer of gene expression regulation not seen in prokaryotes.

These characteristics underscore the inherent differences between early eukaryotes and their prokaryotic contemporaries, independent of the acquisition of mitochondria and chloroplasts. The structural and organizational features of eukaryotic cells provided a framework for increased cellular complexity and the evolution of diverse life forms, setting the stage for the later acquisition of organelles like mitochondria and chloroplasts through endosymbiosis, which further distinguished eukaryotes from prokaryotes.

Question: What are the advantages and disadvantages of linear chromosomes compared to circular ones?

Linear chromosomes, found in eukaryotic cells, and circular chromosomes, typical of prokaryotic cells (bacteria and archaea), each come with their own set of advantages and disadvantages, reflecting their suitability to different cellular complexities and life strategies.

Advantages of Linear Chromosomes

-

Support for Complexity: Linear chromosomes are well-suited for complex organisms. They allow for the organization of a large amount of genetic material and facilitate the intricate regulation of gene expression, which is crucial for the development and functioning of multicellular organisms.

-

Specialized Regions: Linear chromosomes have specialized ends called telomeres that protect the chromosome from deterioration or fusion with neighboring chromosomes. Telomeres also help in solving the end-replication problem by providing a mechanism to replicate chromosome ends using the enzyme telomerase.

-

Recombination and Genetic Diversity: Linear chromosomes facilitate genetic recombination through crossover events during meiosis, promoting genetic diversity. This genetic variation is a key factor in evolution and the adaptability of populations to changing environments.

Disadvantages of Linear Chromosomes

-

Replication Challenges: The end-replication problem is a significant issue for linear chromosomes. DNA polymerase can replicate DNA only in one direction and cannot copy the very ends of chromosomes (telomeres), leading to their gradual shortening with each cell division, which is implicated in aging and cell senescence.

-

Higher Risk of Damage: Linear chromosomes may have a higher risk of breakage, which can lead to genetic disorders or cell death. While mechanisms exist to repair such damage, the complexity of these processes and the potential for errors increase with chromosome length and number.

Advantages of Circular Chromosomes

-

Efficient Replication: Circular chromosomes do not have ends, thus avoiding the end-replication problem. This allows for the complete replication of the genetic material without losing any significant portion of DNA sequences at the ends.

-

Simplicity and Compactness: The circular form is efficient for the compact packaging and organization of genetic material in the relatively smaller cells of prokaryotes. It supports rapid replication and division, advantageous for fast-growing bacteria and archaea.

Disadvantages of Circular Chromosomes

-

Limited Size: Circular chromosomes are generally smaller than linear ones, limiting the amount of genetic information they can carry. This constrains the complexity of the organism and is one reason why most prokaryotes are unicellular.

-

Reduced Genetic Diversity: The absence of sexual reproduction and reduced opportunities for genetic recombination in organisms with circular chromosomes can limit genetic diversity, potentially making them less adaptable to environmental changes compared to eukaryotes with linear chromosomes.

In summary, the structure of chromosomes—linear in eukaryotes and circular in prokaryotes—reflects evolutionary adaptations to their respective cellular and organismal complexities, life cycles, and environments. Each form has evolved to optimize the balance between genetic stability, diversity, and adaptability.

Question: What synapomorphy defines the eukarya?

A synapomorphy refers to a trait or feature that is shared among a group of organisms and is unique to them, having evolved in their most recent common ancestor and passed down to all its descendants. For the domain Eukarya , several synapomorphies define and distinguish eukaryotic organisms from those in the domains Bacteria and Archaea . However, one of the most fundamental and defining synapomorphies of Eukarya is the presence of a nucleus that contains the cell’s genetic material, enclosed by a nuclear envelope . This feature is a hallmark of eukaryotic cells and is not found in prokaryotic organisms (bacteria and archaea), which have their DNA located in a nucleoid region without a surrounding membrane.

Other notable eukaryotic synapomorphies include:

- Membrane-bound organelles (such as mitochondria and, in photosynthetic organisms, chloroplasts), which allow for compartmentalization of cellular functions.

- A complex cytoskeleton consisting of microtubules, intermediate filaments, and actin filaments, providing structural support and facilitating cell movement, shape changes, and intracellular transport.

- Linear chromosomes associated with histone proteins , allowing for the organization and regulation of large genomes.

- The process of mitosis for cell division, ensuring accurate segregation of chromosomes into daughter cells.

- Sexual reproduction involving meiosis and fertilization, contributing to genetic diversity.

The nucleus, as the defining feature, coupled with these additional complex traits, sets eukaryotes apart from prokaryotes, supporting a wide range of life forms and complexities, from single-celled organisms to multicellular plants, animals, and fungi.

Question: What benefits does the nucleus offer to eukaryotic cells, and what evolutionary pressures led to its development?

The nucleus, a defining feature of eukaryotic cells, provides several significant advantages that have contributed to the evolutionary success of eukaryotes:

-

Genetic Material Protection: The nucleus encloses the cell’s genetic material, protecting DNA from damage caused by cellular metabolic processes. The nuclear envelope separates the DNA from potentially harmful enzymes and chemical reactions occurring in the cytoplasm.

-

Regulation of Gene Expression: The separation of the nucleus and cytoplasm allows for a more controlled and sophisticated regulation of gene expression. This compartmentalization enables the cell to regulate the transcription and processing of mRNA before it is translated into proteins in the cytoplasm, enhancing the efficiency and specificity of protein production.

-

DNA Organization and Replication: The nucleus provides a structured environment where DNA is organized around histones and into chromosomes. This organization facilitates the efficient replication and repair of DNA, as well as the segregation of chromosomes during cell division, ensuring genetic stability and integrity.

-

Increased Complexity and Specialization: The presence of a nucleus supports the development of larger and more complex genomes, which in turn enables the evolution of more complex organisms with specialized cells and tissues. This complexity would be difficult to achieve without the regulatory and organizational benefits provided by the nucleus.

The nucleus likely evolved as an adaptation to the challenges and opportunities presented by increasing cellular complexity. Several hypotheses suggest the nucleus evolved to:

- Protect DNA from the damaging reactive oxygen species produced by mitochondria, which were acquired by early eukaryotes through endosymbiosis.

- Manage the increased genetic information needed for more complex cellular functions and multicellularity, requiring enhanced regulation of gene expression and protein synthesis.

The evolution of the nucleus was a pivotal event in the history of life, enabling eukaryotes to exploit new ecological niches, develop complex multicellular organisms, and diversify into the myriad forms of life observed today.

Question: Why have prokaryotes continued to thrive and exist alongside eukaryotes, despite the evolutionary advantages provided by the eukaryotic nucleus?

Prokaryotes, despite the emergence of eukaryotes with their complex cellular structures and nuclei, continue to flourish for several reasons:

-

Ecological Versatility and Adaptability: Prokaryotes, including bacteria and archaea, can inhabit a wide range of environments, from extreme heat and cold to acidic and alkaline conditions , where eukaryotes cannot survive. Their simple cellular structure allows them to rapidly adapt to changing conditions.

-

Rapid Reproduction: Prokaryotes reproduce quickly through binary fission , allowing for rapid population growth and the ability to quickly exploit available resources. This rapid reproduction also enables fast genetic changes and evolution, helping prokaryotes adapt to new environments or changes in their current habitats.

-

Metabolic Diversity: Prokaryotes exhibit a remarkable range of metabolic pathways that allow them to utilize a wide variety of energy and carbon sources. This metabolic versatility enables them to thrive in environments that are inhospitable to eukaryotes.

-

Mutualistic Relationships: Many prokaryotes form symbiotic relationships with eukaryotes , providing essential services such as nitrogen fixation, digestion, and protection against pathogens. These relationships have allowed prokaryotes to persist by directly linking their survival to that of eukaryotic hosts.

-

Genetic Flexibility: Prokaryotes can exchange genetic material through horizontal gene transfer , allowing them to rapidly acquire new traits and resistances. This genetic flexibility is a significant advantage in rapidly changing environments.

The presence and success of prokaryotes, despite the evolutionary advantages of eukaryotes, highlight the complexity of evolutionary processes. Rather than a simple progression where more “advanced” organisms replace “simpler” ones, evolution involves a multitude of adaptations and strategies that allow different life forms to coexist and fill various ecological niches. Prokaryotes' continued existence and prosperity underscore their unparalleled adaptability and the fundamental role they play in Earth’s biosphere.

Question: Why did eukaryotes evolve from prokaryotes, and what drove the development of increased complexity in eukaryotes, given the success and adaptability of prokaryotes?

The evolution of eukaryotes from prokaryotic ancestors represents a pivotal moment in life’s history, driven by unique evolutionary pressures and opportunities rather than the inadequacy of prokaryotic life forms. Several factors contributed to the emergence of eukaryotes and their path toward increased complexity:

Exploitation of New Niches

The evolution of eukaryotes allowed for the exploitation of ecological niches that were inaccessible to prokaryotes. The increased cellular complexity of eukaryotes, including compartmentalization and the ability to process information more efficiently, enabled them to utilize resources in different ways and occupy new environments.

An example of how eukaryotes exploited new ecological niches through increased complexity is the development of photosynthesis in plants. While photosynthesis itself originated in prokaryotic organisms (such as cyanobacteria ), the endosymbiotic event that led to the formation of chloroplasts in ancestral eukaryotic cells allowed for a significant evolutionary leap. This event gave rise to the plant kingdom , which harnessed sunlight to convert carbon dioxide and water into glucose and oxygen on a scale and with an efficiency that was unprecedented.

Plants, with their eukaryotic cell complexity, including a nucleus, endomembrane system, and chloroplasts, were able to grow larger and become more structurally diverse than their prokaryotic photosynthetic ancestors. This ability enabled them to colonize terrestrial environments—a monumental step in Earth’s history. Before plants, terrestrial surfaces were largely barren, but the advent of photosynthetic eukaryotes transformed these environments, eventually leading to the rich, biodiverse ecosystems we see today.

The colonization of land by plants required several adaptations supported by their eukaryotic complexity, such as mechanisms for water conservation, structural support to grow upwards against gravity, and reproductive strategies that did not rely on water for fertilization. These adaptations not only allowed plants to thrive in terrestrial niches but also fundamentally altered Earth’s atmosphere and provided the foundation for terrestrial food webs.

Endosymbiotic Events

A key event in the evolution of eukaryotes was the endosymbiotic acquisition of mitochondria (and, in the case of plants, chloroplasts). This not only provided eukaryotic cells with a more efficient energy production mechanism but also enabled them to grow larger and support more complex structures and functions.

Increased Genetic Information

The transition to eukaryotic life involved the development of linear chromosomes within a nucleus, allowing for the storage and management of larger amounts of genetic information. This increase in genetic complexity made possible the development of more sophisticated cellular processes and organismal structures.

Linear chromosomes can potentially support more genetic information than circular ones for several reasons, contributing to the increased complexity and adaptability of eukaryotic organisms:

- Segmentation and Organization: Linear chromosomes are segmented into multiple pieces, allowing eukaryotes to have many chromosomes within the nucleus. This segmentation facilitates the organization and management of large amounts of genetic information. Each chromosome can be regulated independently, which enhances the cell’s ability to control gene expression and respond to environmental changes.

- Telomeres and Replication: Linear chromosomes are capped with telomeres, special structures that protect the ends of chromosomes from degradation and prevent them from fusing with each other. Telomeres also help to solve the end-replication problem by providing a buffer zone of non-coding DNA that can be lost during DNA replication without impacting essential genes. This allows cells to maintain their genetic integrity over many generations, supporting the long-term stability and accumulation of genetic information necessary for complex life.

- Recombination and Diversity: Linear chromosomes facilitate genetic recombination through crossover events during meiosis, the process that leads to the production of gametes (sperm and eggs) in sexually reproducing organisms. Recombination shuffles genetic information, creating new combinations of genes that can provide a selective advantage under changing environmental conditions. This genetic diversity is crucial for the evolution and adaptation of complex organisms.

- Complexity of Gene Regulation: The structure of linear chromosomes, along with associated proteins like histones, allows for sophisticated mechanisms of gene regulation. Eukaryotic cells can modify the structure of chromatin (the complex of DNA and proteins) to control access to different genes, enabling finely tuned expression patterns that support complex developmental processes and physiological responses.

In summary, linear chromosomes contribute to the ability of eukaryotic cells to store vast amounts of genetic information, regulate gene expression with great precision, and generate genetic diversity. These capabilities underpin the development of complex multicellular organisms, allowing for the sophisticated structures and functions observed in the eukaryotic domain.

👉👉👉 For the programmers in our audience: Consider the analogy where managing a large program within a single file becomes untenable, necessitating its division into modules or functions to handle its complexity effectively. Similarly, nature has followed this approach by transitioning from the cumbersome and entangled single circular chromosome, which is susceptible to twisting and tangling, hindering its interpretation by ribosomes (much like navigating through a large spaghetti code), to a system of smaller, more manageable units.

Cell Specialization and Multicellularity

Eukaryotic cells' complexity paved the way for cell differentiation and multicellularity. This allowed for the formation of organisms with specialized tissues and organs, leading to a diversity of life forms and survival strategies that were not possible in the prokaryotic world.

Evolutionary Innovation

The evolution of eukaryotes can be seen as an evolutionary innovation that provided new ways of organizing life. The success and dominance of prokaryotes in various environments did not preclude the emergence of alternative life forms. Instead, eukaryotes represent a branch of life that explored a different set of possibilities within the vast landscape of evolutionary potential.

Evolutionary innovation refers to the process through which new structures, functions, or behaviors arise within species over time, contributing to biological diversity and the adaptation of life forms to their environments. These innovations can lead to significant changes in how organisms live, reproduce, and interact with their surroundings, often opening up new ecological niches or providing novel solutions to survival challenges.

Causes of Evolutionary Innovation

- Genetic Variation: Mutations and genetic recombination introduce new genetic material into a population. Some of these genetic changes can result in novel traits that offer a reproductive or survival advantage, serving as the basis for evolutionary innovation.

- Environmental Changes: Shifts in the environment, including changes in climate, geography, the availability of resources, or the presence of competitors and predators, can create new selective pressures. These pressures can drive the evolution of novel traits that allow organisms to adapt to their changing surroundings.

- Ecological Opportunities: The colonization of new habitats or the extinction of competitors can open up ecological niches. Organisms that evolve traits allowing them to exploit these niches can experience rapid diversification and innovation.

Why Existing Life Forms Do Not Prevent Innovation

- Diverse Ecological Roles: The biosphere is incredibly complex, with a vast array of ecological niches. Existing life forms might occupy many niches, but they cannot fill all possible roles within ecosystems. New innovations allow organisms to exploit untapped resources or create new ecological interactions.

- Adaptive Radiations: When a novel trait allows an organism to access a previously unexploited niche, it can lead to an adaptive radiation, where a single ancestral species rapidly diversifies into a wide variety of forms specialized to different environments. This diversification can occur even in the presence of established competitors. 3.Dynamic Environments: The environment is constantly changing, which can alter the competitive landscape. Traits that were once advantageous can become less so, and previously unexplored strategies can become viable, allowing for the emergence of innovations.

- Co-evolution: The evolutionary changes in one species can drive changes in others. This dynamic interplay can lead to evolutionary arms races and symbiotic relationships, both of which can foster innovation.

In summary, evolutionary innovation is a fundamental aspect of biological evolution, driven by genetic variation, environmental changes, and ecological opportunities. The existence of established life forms does not preclude innovation because the complexity of ecosystems and the dynamic nature of environmental conditions ensure that there are always new niches to exploit and new evolutionary challenges to overcome. This ongoing process contributes to the incredible diversity of life on Earth.

The emergence of eukaryotes and their subsequent evolution towards increased complexity were not a reflection of prokaryotic inadequacy but an exploration of new evolutionary pathways. Both prokaryotic and eukaryotic life forms have thrived, each exploiting their unique adaptations to succeed in different ecological contexts. Evolution is not a linear progression towards complexity but a branching process of diversification where different forms of life emerge and adapt to the myriad opportunities and challenges presented by the Earth’s dynamic environments.

Share

Tags

Counters