How I overcame depression

Posted on September 3, 2024 • 14 minutes • 2878 words

Table of contents

Experience of Self-Healing

Since my time in the army, I developed the habit of not treating the flu. Why from the army? Because in the army, they didn’t treat us for the flu. If it was a serious illness, we went to the infirmary (quarantine) or the hospital (treatment). I want to specifically point out that no treatment was provided in the infirmary because there were no medications. The only purpose of being placed in the infirmary was to isolate the patient. Getting into the hospital required a solid reason, like a concussion or self-harm. I don’t remember any cases of concussions in our unit, but self-harm was frequent. Although, it wasn’t real, just simulated. Cut your hand with a razor, and you’d be sent to the hospital and then discharged. A couple of weeks later, you’d come back, pack your things, and go home.

The downside of this “discharge” was that you were sent home with a psychiatric certificate. This meant no driver’s license, no gun permit, and potential problems finding a job because now you were officially “crazy.” But that didn’t stop anyone.

I remember one week when eight people went to the “loony bin.” All of them tried to simulate suicide using a rope, a stool, and an iron hook in the infirmary washroom. The unit commander got so fed up that he ordered the hook to be sawed off, and the “suicides” sharply decreased.

But soldiers are inventive. For example, here’s a method for a quick discharge I learned from my comrades:

- Eat some kind of construction mixture.

I won’t tell you exactly what kind of mixture—it’s just that I don’t remember, and if I did, I wouldn’t tell you.

- Drink as much liquid as possible.

- Jump from a height of about two meters.

“And what’s the point of that?” I was surprised since all the necessary “resources” for discharge were available in unlimited quantities at the time.

You have to understand this from a medical perspective, like when someone recommends drinking celandine or rubbing mushroom tincture on your earlobe. You wonder what the healing effect could be.

“This will drop your kidneys,” my comrades told me. Where exactly they drop, I didn’t ask. And to this day, I remain in the dark.

But let’s return to army treatment (specifically for colds and the flu). The rule was: if a soldier’s temperature wasn’t above 38°C, he was considered healthy and continued fulfilling his duty to the motherland. If it was higher, the soldier was temporarily relieved from duty.

That didn’t mean he was sick since no one was going to treat him anyway. But he wouldn’t work (I served in a construction battalion); instead, he’d sit in a warm barrack. That was the extent of the treatment. His daily routine wouldn’t even change: wake-up, lights out, formation, going to the mess hall—all according to regulations. Lying down was forbidden. You could write letters if you wanted or watch TV. And you’d better avoid being seen by the sergeant, who had his own views on illnesses and treatment methods.

After returning from the army, I stopped paying attention to colds and the flu. Army experience showed that if the flu wasn’t treated, it passed in about four days. The math wasn’t in favor of treatment, as you might notice. Of course, someone might argue otherwise, but in the army, I simply had no other choice. And after I returned, there was no point in taking anti-flu medications or antibiotics because I had proven to myself that colds and the flu were best treated by avoiding military duties. So I didn’t treat myself. And if someone asked me, “Why don’t you treat yourself?” I would explain it as a habit. I got used to not treating myself in the army, so I continue not to.

My attitude toward fever is the same: if I have the strength to do something (like writing this article), then there’s no fever. If I have no strength, then there’s clearly a fever, and no thermometer is needed.

A thermometer is certainly a valuable thing if its readings can get you out of school or work.

But if you’re making decisions based solely on how you feel—whether to work or “be sick”—then the thermometer is useless. I just don’t understand why you need to measure your temperature in that case.

If I can work, I work. If I can’t, then I don’t. What my temperature is doesn’t matter. If you think that you might have 40°C and don’t notice, and you’re working to the detriment of your health—that’s nonsense! And if the thermometer shows normal, but you have no strength, following its recommendation is also foolish. You need to follow your own feelings. That’s the best metric for assessing your physical condition.

Depressive Metrics

I don’t want to get ahead of myself right now and explain how my thoughts on not treating the flu relate to depression. They do. Very directly. But you’ll find out about that a bit later.

When people say they have depression, it can mean anything:

- “I have depression; I need to eat a sweet pastry.”

- “Chocolate really helps with my depression.”

- “If I can’t sleep, I start feeling depressed.”

- “I don’t like it when it rains, I get depressed.”

- “I had depression in the morning, but by evening I felt better.”

- “Yesterday, I really had a serious case of depression.”

- “When I look at his photo, I get depressed.”

- “When I think about tomorrow, depression hits me.”

And so on, and so on. I used to think that way, probably. And I probably said things like that until I experienced what real depression is. And when it’s real depression, no pastry helps, no chocolate, no sunny day outside. Nothing helps because you no longer want the most important thing: to live. How can someone treat depression with sports or active leisure? I honestly don’t understand. You don’t want to live—that’s what depression is. Being in this world becomes unbearable—that’s what depression is. If I wanted anything, it would be just one thing: to die. But even that I didn’t want because you have to want, desire, and do something for it. And I didn’t want anything, including living. That’s what depression is.

I didn’t know what to do. Even if I had known from reading Dr. Kurpatov’s useful book, I wouldn’t have done anything because I had no desire to do anything and no energy either. The only thing I could do was nothing. And see no one. And hear nothing. The presence of anyone around was unbearable torture. Working was out of the question. I didn’t make any decisions to quit my job—there was nothing like that. The job just ceased to exist for me.

I Stopped Going to Work

I didn’t feel any relief, but I didn’t seek it either. I didn’t want to live, and just the thought of trying to come to terms with it made me feel nauseous and disgusted. To be fair, I didn’t have such thoughts. But people constantly reminded me, reminded me.

That life is beautiful and amazing. That things aren’t as bad as they seem. I remember well the excruciating pain those words caused. It’s that very hell, with devils and frying pans, that religious grandmothers love to talk about. I don’t know if heaven and hell exist, but I know for sure that depression is hell, and the people who tell you how wonderful someone else’s life is are the devils.

Maybe it wouldn’t be so bad if they didn’t say anything. Then it would just be “not life.” But they keep reminding you how great and beautiful life is, and you enter hell because for you it’s utterly unthinkable, but they keep telling you that it’s possible, and all you need to do is want it, and the results will follow.

It’s like singing to a blind person: “How beautiful this world is, look.” They can’t, do you understand?

I Stopped Interacting with People

I stopped answering the door. I stopped responding to calls. It was easiest to be among complete strangers—easier because I didn’t exist for them, and that was very close to what I felt, as I didn’t exist for myself. Perhaps if one of those strangers started crying, I would cry too. As if someone finally understood me. That nothing could be fixed. As if they had come to visit my grave—that’s the feeling.

On the contrary, people I knew well brought only despair and sadness. Not because they were particularly bad. No. It’s just that they were emotionally close to me, and that prompted them to help and support a close person in a difficult moment. And nothing in the world is more painful in such moments than such “support.” It’s like telling a mother who has just buried her child how wonderful and amazing life is.

I Stopped Doing Anything at All

I mostly slept. As much as I could. Anytime, day or night. I don’t remember if I had any special dreams worth mentioning. I don’t remember. I often hear people complaining about nightmares and associating them with depression. I don’t know. For me, the most terrifying nightmare was reality. It wasn’t scary to sleep, but to wake up. Sleep, even temporarily, allowed me to hide from it.

If I couldn’t sleep, I just lay there, my face pressed against the wall. I’d lie there, lie there, and then drift back into sleep. I only got up out of necessity. To go to the bathroom. To drink water. Or when hunger started gnawing at me, I’d eat something to suppress it.

I had no money. I had a lot of pickles. Salt, noodles, a lot of old potatoes. I’d toss noodles, potatoes, and pickles into a pot, boil it up in a big pot (so it would last), and eat. I didn’t have any “craving” for food. I probably could have chewed on hay just to dull the hunger. Once the hunger subsided, I couldn’t eat anymore. Physically couldn’t. I’d put my concoction in the fridge and go back to pressing my face against the wall.

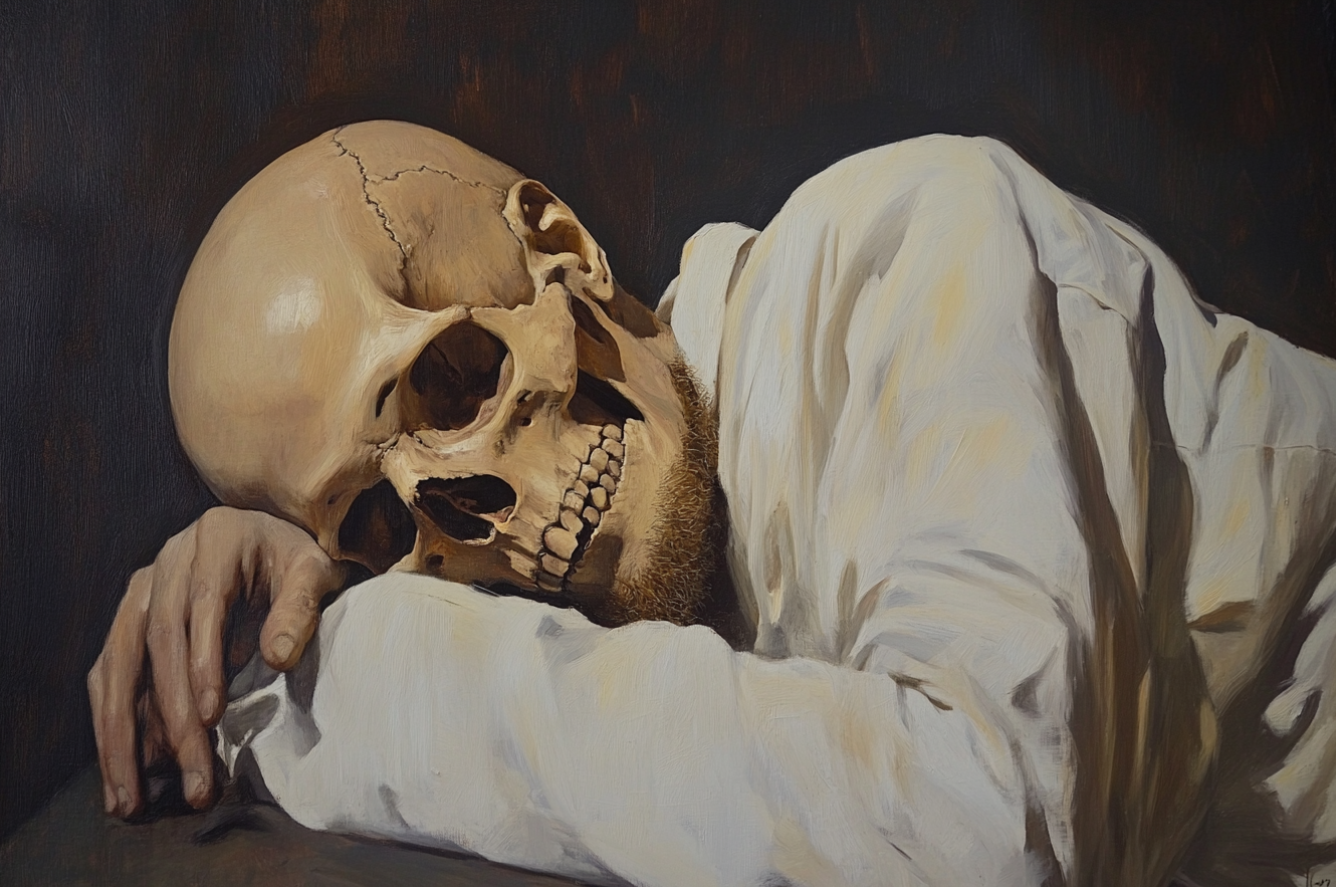

I Denied Myself Existence

Time stopped. It lost all meaning. What the clock said didn’t matter. I didn’t know what to do next. No, not like that. There was no “next.” The future didn’t exist. There wasn’t a single thought, not even a secret one, that one day I’d wake up, and all this would pass, and I’d feel better. There was simply no “tomorrow.” There was unbearable “today” and an alien “yesterday.” There were photos of some person who no longer existed. Books he had read. Diaries he had written. Their presence was a constant, painful reminder of some “other life” that was no more.

It was like someone who had lost their legs returning home to find their shoes still standing in the hallway. I think it was something like that. A constant reminder that this will never, ever return to you.

So I methodically began to destroy everything that reminded me of my “past life.” I took out the photos and cut them into tiny pieces with big scissors. I even found some sense in it. Of course, I knew that once I had cut everything, it would all end, but I didn’t care (and couldn’t care). Everything had already ended, in reality. Meanwhile, I had a lot to destroy. Photos. Diaries. Books. Everything that even remotely reminded me of that “other life.”

I had many photos. Many books. Many different notebooks and diaries. I tore the notebooks and books into separate pages and then shredded them into tiny pieces. I cut the photos with scissors. I packed the paper “mash” into bags, and when there were many, I took them outside and threw them into the trash bin. At first, I wanted to burn them, so I went out at night, but I didn’t. There would be too much smoke, and someone might start yelling, and I was already nauseated as it was.

How long this went on, I can’t say for sure. A month, two months? Yeah, probably something like that. The thought of doing something to myself brought nothing but pain. I couldn’t. Not because it was scary, no. Because it was painful. Even the thought that it could be done made me want to scream and climb the walls. But I found something I could do to myself.

Photos. Letters. Army diaries. Literary attempts. And the more I did it, the easier I felt.

And Something Subtly Changed, And I Realized I Could Live On

This happened before I had finished with all my photos and letters. There was still a little left, but suddenly I found myself wanting to write something new. In a clean, new notebook. I wanted to open a notebook with squares, a large new notebook.

And I wanted different pens, ones that wrote in different colors. Red and green. And blue. And black. I really wanted them to be multicolored pens. There were no thoughts yet about what to write, but there was already a desire to write something. Sometimes we say we want to “start life with a clean slate.” I experienced this literally. But there were still many “dirty” pages from my past life on the floor, so I didn’t write anything for now. I decided to finish off my past. And until the last sheet of paper that reminded me of that past was destroyed, I didn’t rest.

Something had changed. My emotions were returning, my desires were returning. I regained my appetite and interest in communication. Thoughts came to me that seemed important, and I wanted to write them down. I started writing in a notebook, and I liked it. The notebook hasn’t survived to this day—I lost or threw it away—but that doesn’t matter. The past ceased to mean anything to me. Only vague memories remain of it. If I want to “resurrect” them, there will be these writings. If not, there will be nothing left.

When the Body Aches and When the Soul Hurts

Now I’m going to tell you something that might be hard to believe. I don’t care whether you believe it or not. Just think about it.

👉 Depression is a Post-Mortem Experience

Similar to what a person experiences in clinical death. Only with depression, the person’s body continues to live. You can move. Eat. Go to work. Be a useful member of society.

Dead, but useful. No one would ever guess that this person is dead. Especially since there are medications that “revive” their physiological functions: increased physical activity, reflex and emotional “response” to external stimuli, partial restoration of willpower, normalization of blood circulation, and so on.

This isn’t some Voodoo magic, just basic psychiatry. And the drugs that can turn a “dead” person into a zombie who “comes to life” are sold in any pharmacy.

Depression is more than just the absence of meaning. Like wanting to do something. Depression is the realization of the impossibility of living any further.

It’s when you understand that life has ended, but your body continues to exist.

You can move your legs or arms, do something with your body. But you can’t do the most important thing: live. There’s only one thing left: do something with your body. But without a soul, without its owner, the body doesn’t want to do anything. There are no desires at all. There are needs. The “empty” body doesn’t need sports, holiday gifts, or the meaning of life.

When I had the flu, I always explained my refusal of treatment as a “habit.” That in the army, no one treated us, and it didn’t complicate the recovery process at all. They just freed us from work, and that was the treatment. And I always emphasized that “they didn’t treat us,” as if my refusal to take medicine was the treatment itself.

Only recently did I understand that it wasn’t about refusing medicine but about refusing work. The treatment was that we were allowed not to do what was objectively hard or impossible.

There’s no healing effect from refusing medicine. You just need to stop doing what is done with difficulty or “through can’t-do.” And, on the contrary, do what you want to do. That’s all the treatment there is.

And what does your body want when it’s sick? Think about it. The body doesn’t want aspirin or cough tablets. But it may want rest. To be warm (hide under three blankets). Something hot. To rest. To sleep. Silence and less light. And that’s more than enough for a quick recovery.

I didn’t fight my depression. My hands dropped, and I didn’t try to lift them. I couldn’t find the strength to change anything, so I left everything as it was. I couldn’t force myself to go anywhere, so I lay down. I wanted oblivion, and sleep helped me forget. I only did what I wanted. And I didn’t want anything. Nothing. So I did nothing. Maybe that’s what saved my life.

Thank you to the author of the article, a member of the ScienceChronicle.org team, Ph.D. in Psychology, Michael Budler. Your insights and expertise are greatly appreciated.

Share

Tags

Counters